|

「希望は子どもたち」 敵国へ嫁いだ日本女性, BuzzFeed Japan, Feb. 3, 2016 (in Japanese) http://www.buzzfeed.com/sakimizoroki/fall-seven-get-up-eight-jp#.rejoRPpP2 Washington Japanese Women's Journal, winter 2016 edition http://www.wjwn.org/views/article.php?NUM=V-0534 Rosebud Film Festival Shows Off D.C. Region's Filmmakers, Jan. 29, 2016http://wamu.org/news/16/01/29/rosebud_film_festival_shows_off_dc_regions_filmmakers Our interview in "The Mixed Experience Podcast," Sept. 28, 2015 http://www.themixedexperience.com/season-3-episode-3-fall-seven-get-up-eight-filmmakers-interview/ Asahi Shimbun newspaper (English edition, Aug. 13, 2015) Newstalk (Dublin, Ireland) 12-min interview with war bride daughter Lucy Craft, Aug. 26, 2015

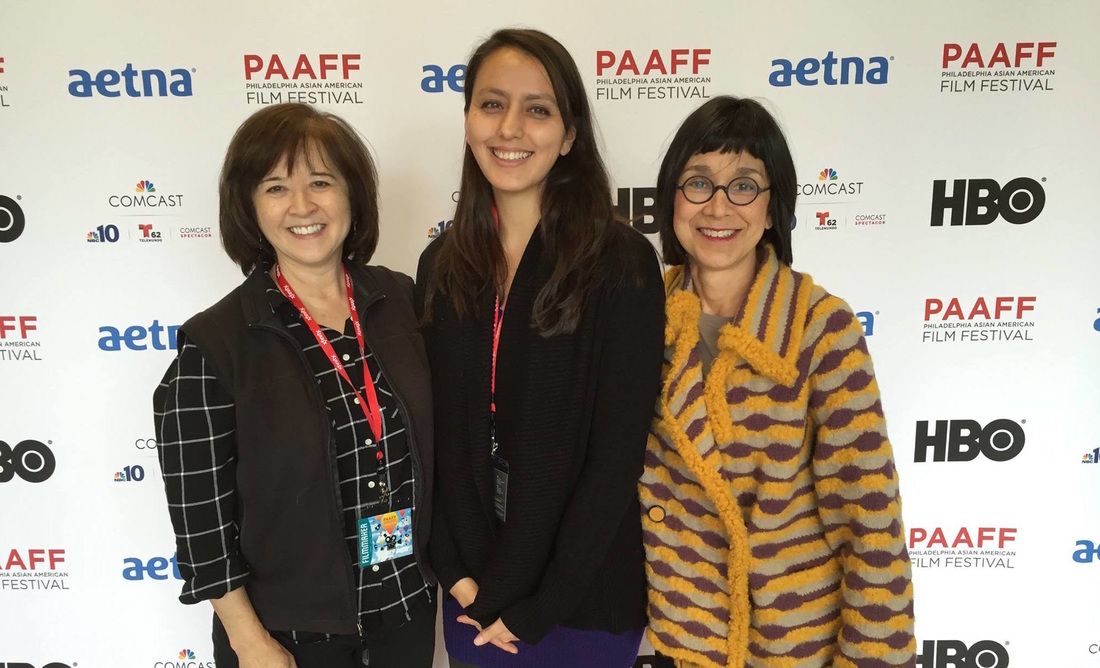

http://www.newstalk.com/podcasts/Moncrieff/Highlights_from_Moncrieff/102808/ The_Japanese_War_Brides_of_WWII BBC News magazine, Aug. 16, 2015 http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-33857059 Virginian-Pilot, Aug. 15, 2015 http://hamptonroads.com/2015/08/daughters-make-film-tell-japanese-war-brides-stories Elmira Star-Gazette, July 15, 2015 http://www.stargazette.com/story/news/local/2015/07/17/japanese-war-brides-story-told/30294911/ Our film, "Fall Seven Times, Get Up Eight: The Japanese War Brides" won another award! We got the Best Short Documentary award at the Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival, PAAFF, http://phillyasianfilmfest.org/ The venue was full and afterwards we had so many questions, they had to shut it down so the next series of films could run. Everyone agreed they wanted to see more and hoped we try to expand it out to an hour! #PAAFF

We are delighted the news that we received the "Best Documentary Short" Audience Award at the Boston Asian American Film festival!Wonderful news! Our film will make its World Premiere on BBC World News on Saturday, Aug. 15 in commemoration of V-J Day. Check the broadcast schedule for local airtimes. http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/n3cszlh9

Professor emeritus Shigeyoshi Yasutomi, who recently retired from Tokyo’s Kaetsu University, has devoted his career to the study of Japanese war brides and is one of the world’s leading experts on a subject few have examined closely. His interest began when he was still a boy, growing up in small-town Niigata Prefecture, northern Japan. “An American GI who used to work at Misawa Air Base moved with his Japanese wife and kids to our town,” he recalls. “We used to call him ‘America-san’!” Prof. Yasutomi would go on to major in minority studies at the University of Nevada in the late 1970s, spending school breaks playing piano at Japanese pubs in southern California. In those pre-karaoke days, he churned out requests for Japanese enka and minyo (Japanese ‘country’ music and traditional songs) for a mostly Japanese-American clientele. A few of his customers were Japanese war brides, and one family befriended the young graduate student. The woman’s son was about his own age, Yasutomi recalls, and one day, he seemed troubled. “While we were driving, he suddenly said, 'what did my mother do in Japan? How did my parents meet?' It sounded like this had been bothering him for a long time - that he’d heard a lot of negative things about war brides.” Having spoken with the war bride at length about her past life in Japan, Yasutomi was able to reassure her son that his parents had been introduced through friends. The woman had worked a conventional blue-collar job before marriage. “The son seemed relieved," Prof. Yasutomi says. "I realized then what a hurtful term ‘war bride’ had become. I thought, we must set the record straight about the war brides— for the sake of their children.” Prof. Yasutomi went on to do just that, tirelessly publishing research on war brides and guiding other scholars since the 1980s. He has unflaggingly and generously shared his vast knowledge with us over the last few years - and via our documentary project, we seek to carry on his legacy, faithfully portraying the life and times of the Japanese war brides. Above, slide show by Karen, from the annual gathering of the Nikkei International Marriage and Friendship Club, an organization of Japanese war brides, their families and friends based on the west coast. Founded in the 1980s, the group's numbers are dwindling, but the womens' energy, enthusiasm and sheer joie de vivre remain undimmed. We were inspired and honored to be allowed to join them last May in Denver.

I used to pick blueberries alongside my Japanese war bride mother when my dad, a sailor, was out at sea. We lived in a trailer in rural Michigan for two years. She had only arrived in the US a few years before and didn't know putting a five-year-old in the fields to pick wasn't exactly proper parenting in the US. The farmer was not taking advantage of child labor, rather doing my mother a favor by allowing her to bring her children into the fields. I took advantage of that opportunity. I made 10 cents a quart and my little fingers picked the berries very carefully but quickly. I often earned a dollar or more a day. My memories of those times are pleasant. I took great pride in contributing to the family and being in the fields. My younger brother played with the son of the farmer and my little baby sister sat beside us playing in the dirt. And to this day, l love blueberries, especially those grown in Michigan.  An Indian restaurant in Tokyo seemed the perfect venue for talking mixed-race issues with visiting UC-Santa Barbara Prof. Paul Spickard, who was introduced to us by Tokyo-based colleague Kaori Mori. Prof. Spickard draws double-takes at academic conferences - "What's the white guy doing here?" - but having grown up among the children of Japanese war brides in Seattle, the subject is second nature and he has written prolifically about race, ethnicity, and the Japanese-American community. Even as a child, he noticed that war bride kids tended to be shut out of the Japanese-American community, whether it was not being eligible for Cherry Blossom Queen, or being excluded from Nisei sports leagues. "The Japanese community in Seattle didn't want to have anything to do with war brides," he recalls. But later, as traditional Japanese communities struggled to survive, "the irony is that war brides were the ones who held the Japanese-American community together," working as waitresses in Japanese restaurants, helping organize cultural festivals, caring for Japanese-American seniors." Yet even today, "the community doesn't want to recognize them." This fraught relationship between the war brides and the larger Japanese-American community is a theme we will explore in our project. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed